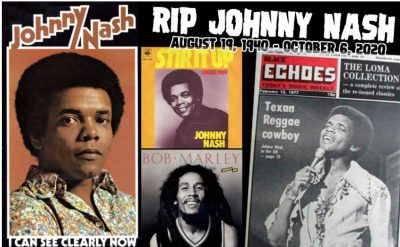

It was a little over a year ago that friends and family gathered at Fountain of Praise Church in 5 Corners to celebrate the life of Johnny Nash, Houston’s great soul, reggae and pop singer and songwriter, producer and music executive. His soul then commended to heaven, it is now up to us to maintain and bolster his legacy, and one of the best ways to do that is to see to it that Johnny Nash takes his rightful place alongside global superstars Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff — singers for whom Nash paved the way — in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

For those reasons and many others, as we shall see. Over the last few months I have assembled what I believe is the most accurate and extensive written telling of the life story of Johnny Nash. And perhaps the only one. (Click here for Part 1, here for Part 2, and here for Part 3).

For those reasons and many others, as we shall see. Over the last few months I have assembled what I believe is the most accurate and extensive written telling of the life story of Johnny Nash. And perhaps the only one. (Click here for Part 1, here for Part 2, and here for Part 3).

To assess his many varied contributions to the music and entertainment world demands such detail. His career was almost uniquely fragmented into phases, and he was just on the verge of doing more than excelling at each, before he would maddeningly move on to the next. Perhaps when the young Johnny Mathis crooner thing played out, he could have moved in a more soulful direction and emulated Sam Cooke and then continued on to rival Marvin Gaye. When he went into acting, had he kept at it, perhaps there would have been a future in him as the world’s foremost sensitive Black leading man of the 1960s and ‘70s, bridging the gap between Sidney Poitier and….Denzel Washington, outside of the more macho actors of the Blaxploitation era such as “Dolemite.”

But by then he and his producer and business partner Danny Sims had moved on to gritty soul, and once more he seemed on the Sam Cooke track, until fate took the two of them to Jamaica, where he introduced the world first to rocksteady music and then reggae music, and then to first the songs of Bob Marley and then the man himself, not to mention bandmates Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer.

Make no mistake — Johnny Nash “discovered” Bob Marley. Not Danny Sims. Certainly not Chris Blackwell, the white Jamaican who would make Marley famous worldwide in the early 1970s and went on to build the Island Records dynasty.

All of this came only after Nash and Sims sold Marley’s contract to Blackwell in London. It was Nash, not Blackwell, who came back to his Kingston digs from an underground Rastafarian party / jam session in 1968 telling Sims about this exciting and charismatic singer named Bob Marley. And it was Sims and not Blackwell who was the first non-Jamaican to record Marley.

While you often see pop musicians Paul Simon and Eric Clapton credited as the great popularizers of reggae in America and the West, Nash beat them to the charts by several years with his “Hold Me Tight.” By the time Clapton and Simon caught up with Nash, he’d moved on to the reggae/pop fusion that resulted in his transcendent, luminous and immortal biggest hit, “I Can See Clearly Now.”

In between, he had several smaller hits with songs like the Marley composition “Stir It Up” and pushed the envelope creatively with a bold and fascinating attempt at a fusion of country and western with reggae on the Peter Tosh composition, “There are More Questions Than Answers.”

Which could also be applied to the mystery of why Johnny Nash is not yet in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Of Blackwell it has been famously said that he is “the single person most responsible for turning the world on to reggae music.”

Those words come from the speech that accompanied Blackwell’s induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, where he is enshrined alongside Simon and Clapton (for whom reggae was just a phase; not knocking them as enshrinees) and also Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff — a silken-tenored Jamaican for whom Nash helped pave the way. (And who returned the favor in 1993 with his worldwide hit reprisal of “I Can See Clearly Now.”)

Without Nash’s talent-scouting and early performances of Marley’s songs and role in taking him to London, it’s eminently possible that he, and by extension all of reggae music, would be a cult style today, not unlike the one that arose around vintage Cuban “son” music in the aftermath of the Buena Vista Social Club phenomenon, rather than something like the soundtrack to the Global South.

I go on at length about this for a reason. The world knows “I Can See Clearly Now” and will for as long as music exists — it is one of those songs that exist on a higher plane with such gifts from the celestial as Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World,” Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?”

Because that song is so very great, it has overshadowed his other hits. Neither Nash nor anyone else did much to aggressively tend his legacy, so it’s forgotten now that “Hold Me Tight” was almost as big a hit as “I Can See Clearly Now,” and he had several others in the top ten and 20 of the USA, Australia, Canada and the UK, including some here of the jazz ballad style he sung as a young teen idol and then more as a smoldering soul man before his Jamaican sojourn. White America hardly knew his name until “Hold Me Tight,” but reading the society pages of Black newspapers coast to coast revealed to him to be an A-list celebrity throughout much of the ‘60s.

On just the musical front, much slimmer resumes than that have punched tickets to rock hall in Cleveland. Frankie Lymon is in — now there was real one-hit wonder, but even with his “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” his tragic, drug-shortened career as a Black teen idol was only marginally more successful than Nash’s roughly concurrent one.

On just the musical front, much slimmer resumes than that have punched tickets to rock hall in Cleveland. Frankie Lymon is in — now there was real one-hit wonder, but even with his “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” his tragic, drug-shortened career as a Black teen idol was only marginally more successful than Nash’s roughly concurrent one.

Percy Sledge is in, and nobody knows him for anything but “When A Man Loves A Woman.” (Contrast his track record to the Houston area’s own Joe Tex and wonder why Sledge is in and Tex is not).

Seemingly every doo-wop band to stake out a corner in some big eastern city in the 1950s is in, too; achingly obvious is the fact that this was the music that so many of the Hall’s voters — also hailing from those cities — cut their baby teeth on rather than any true enduring colony that would set it apart from regional stars from Texas, like Gatemouth Brown or Doug Sahm, who are not in.

Anyway, back to my original point — while Nash has a purely musical resume worthy of induction on its own merits, his spearheading the popularity of reggae is criminally underrated.

I come from a family that is credited with helping discover or make the earliest recordings of many musical artists from Leadbelly to Muddy Waters to Son House to Woody Guthrie, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle and Hayes Carll. It’s a knack we have, but the thing is, we’ve done it primarily as scholars and/or simple lovers of the music, just out of an impulse that compels us to say, “Well wait ‘til you hear this!”

The thing is, none of us has made much money at it. Some, but not a lot — that would be left to the Chris Blackwell’s of the world, or the Chess Brothers of Chicago. (In the 2008 film “Cadillac Records”, an actor playing a composite of my great-uncle Alan Lomax and my great-grandfather John Avery Lomax is shown recording Muddy Waters on the front porch of his shack in a Mississippi cotton field. Which is about how it went down — it was not a Cadillac record for either Muddy or Alan, though it is forever enshrined in the music collection at the Smithsonian Institution, which was Alan’s mission rather than commercial sales).

Nash had this same talent on an earth-shattering level. Where would today’s world be without Bob Marley? Would reggae have ever amounted to anything but a passing fancy in the early 1970s, like other “world music” trends that have come and gone, like the fads for Brazilian music ginned up by phenomena like “Black Orpheus” or South African music that followed in the wake of Paul Simon’s Graceland album?

Nash, who returned to Houston after closing out his music career,

grew to care less and less about fame or money. He made a new career here of managing horses and his rodeo arena.

He’d had enough of the former in his early career and he had enough of the latter to last him comfortably to the end of his 80-year stay on the planet. In that way, his career resembled that of Bill Withers — he made about 10 of the finest soul songs the world has ever known. He kept his money right, and when he got tired of the music business, he just walked away. And it took an unduly long time, but Bill Withers is now in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

But do you know what the greatest crime in all of this is? Johnny Nash is not only not in the Hall of Fame — he’s never even been on the ballot.

Let’s get him on the ballot and into that Hall. It can be done, but there must be a groundswell, an appeal from those that knew and loved Nash’s music and contributions. This is how many a neglected but worthy baseball player at last found his way to Cooperstown — advocacy. Houston’s music business veterans can start the ball rolling with their contacts in Los Angeles and New York. Nash is, if anything, even more beloved in London and the UK than stateside, so it’s easy to imagine plenty of support from across the pond. Get up petitions. Write letters. Start a website.

Together we can lift the dark clouds that have them blind, and make together that bright, sunshiny day when Johnny Nash takes his rightful place in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

2020 photo collage by reggaeville.com

— By John Nova Lomax