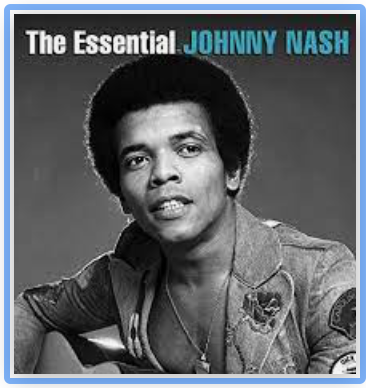

Seldom has the “one-hit wonder” tag been less accurately employed than it was in the case of Johnny Nash. As we mentioned in Part 1 of this story, to call Nash such is a shame and sin and just plain wrong as wrong can be, as in utterly incorrect.

Seldom has the “one-hit wonder” tag been less accurately employed than it was in the case of Johnny Nash. As we mentioned in Part 1 of this story, to call Nash such is a shame and sin and just plain wrong as wrong can be, as in utterly incorrect.

To wit, how could it be that this so-called one-hit wonder, already billed as a “movie, TV, and recording star,” was appearing on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show regularly alongside the likes of Mel Brooks, Bill Cosby, Eva Gabor, Woody Allen, Dirk Bogarde, and Marlin Perkins, of Wild Kingdom fame, in 1964, almost 10 years before “I Can See Clearly Now,” his purported one-hit?

How is it that this one-hit wonder whose “one hit” was still years away had his name constantly in the papers, coast to coast and in the UK, Australia, and Canada, in 1964 and and 1965, either in connection with his starring role in the groundbreaking film Take a Giant Step, his network TV and nationally syndicated radio appearances (he still maintained a connection with Arthur Godfrey), or his headlining shows at swank clubs like Detroit’s Alamo Room, Harry’s American Bar in Miami, and the Sutherland Room in Chicago’s Sutherland Hotel?

Enough on that. Hopefully you get the picture. And a big part of the story was not told in American papers, or in any that are archived on the Internet.

In actual fact, nobody has written the story of Johnny Nash —-

born on Aug. 19, 1940, in Third Ward south of downtown Houston, a southside resident in later decades and funeralized at Fountain of Praise church in the Five Corners District on Oct. 15, 2020 — with half the care and attention it has long deserved. Nobody has looked back at this most disparate though always excellent career and accurately weighed its sum total.

In attempting to do so here, it suddenly has dawned on me that there are few if any popular musicians more deserving of enshrinement in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. To use the Hall’s own words, they are looking for people who “created music whose originality, impact and influence has changed the course of rock & roll.”

By introducing the world to reggae via Bob Marley, and by extension Marley’s fellow Jamaican Hall of Famer Jimmy Cliff, Nash changed the course of rock and roll without singing a note.

“I Can See Clearly Now” is not just a hit; it has transcended that status and exists now on a magical plane alongside songs with that extra something, like Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World” or Glen Campbell’s “Wichita Lineman” or Prince’s “Purple Rain.” And as we keep on saying, that was far from his only hit. The R&RHOF is full of musicians with much thinner resumes than that of Houston’s own Johnny Nash, and to their shame, he has never even been placed on the ballot. That needs to change.

As we shall see…

Bob Marley, Johnny Nash in a Jamaican recording studio

In 1963, Nash met Danny Sims, the man with whom he would collaborate professionally for the last and most fruitful decade of his professional life. With Sims, Nash would score not just the one but a handful of worldwide hits, bring the sounds of Jamaica to the world, and, effectively, “discover” Bob Marley.

Born in Hattiesburg, MS in 1936, Sims was raised in Memphis and the South Side of Chicago. After his Army service ended, he settled in New York, where, according to Sims and others, he forged strong ties with the Gambino crime family. With the mob’s assistance, Sims integrated Midtown Manhattan nightlife by opening Sapphire’s, according to Sims, “the first Black-owned nightclub south of 110th Street.” A silent partner in this and other Sims endeavors was Joseph “Piney” Armone, a Gambino underboss, who in 1965 was about to begin serving a 15-year-sentence for his role in the “French Connection” heroin ring. Paul Castellano, Armone’s boss, would also become partners with Sims, as we shall see.

According to Sims, in 1963, Nash asked for his assistance in promoting his first Caribbean tour. The two of them fell in love with Jamaica, Sims remembered, and it led him to form a booking agency called Hemisphere Attractions, whereby Sims would arrange Caribbean and Central American concerts for some the biggest names in music — Sammy Davis Jr., Brook Benton, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, and even Paul Anka, who he managed for a time.

Nash also hired Sims to be his manager, and in July of 1965, Nash announced that the two of them had founded JoDa Records and wasting no time, Nash released “Let’s Move and Groove,” this nearly forgotten slice of heaven, Nash’s most mature statement to date. Here we hear his velvet tenor — like that of Sam Cooke, simultaneously smiling and melancholy — finally coming into its own, soaring effortlessly above a mighty gospel choir, as seen in this rare, live video.

A writer for the Pittsburgh Courier called it a “stone gas” and predicted this song by “John the Tiger” would hit the very top of the charts, and it almost did — the rhythm and blues charts, anyway, where it reached number four. As for the pop charts, it would stall out in the 90s, and according to Sims, there was a very good reason for that: He’d landed on FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover’s radar, and not even his Mob ties could save him.

Sims told the story years later to reggae scholar Roger Steffens.

“There was a very popular African-American disc jockey in Los Angeles at the time who called himself ‘The Magnificent Montague.’ He played Johnny’s record all the time, and he would yell over the air while it was spinning, ‘Burn, baby, burn!’”

Unfortunately for Sims and Nash, the Watts uprising happened almost the very day they released his biggest hit, and through no fault of their own, “Burn baby, burn!” became a revolutionary slogan.

“I thought I was dead,” Sims told Steffens. In another interview, he recalled getting a threatening phone call from the FBI.

“So many of our people were being killed then. So I decided to get the hell out, and we left for the Caribbean. Our favorite country in the world was Jamaica, so we headed there.”

That meant Sims couldn’t spend the extra time and money marketing “Let’s Move and Groove” to White radio…Which is a shame, because this record had the potential to vault Nash to the very top of the burgeoning soul heap. If there was anyone out there he could potentially fill most of the void left by the December 1964 death of Sam Cooke, it was his long-distance protege Johnny Nash.

But it’s funny how life works out. Nash and Sims would set a new course in Jamaica and Nash’s pop hits would come, albeit in a form neither of them would have foreseen in 1965.

“There are three artists who’ve really influenced me in my singing career,” Nash told the UK’s Melody Maker magazine in 1969. “They are the late Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin and Harry Belafonte. They all have something I wish I had.”

Maybe he wasn’t all the way as great a singer as Sam Cooke. That’s okay, because nobody was: it is to compare Hank Aaron to Willie Mays. And maybe he wasn’t as overtly political, or as prominent for as long, as Harry Belafonte. Strangely, though, his career arc would bear a striking similarity to that of Belafonte’s. Each of them would have a hand in popularizing different forms of Caribbean music a decade apart — as Belafonte was to calypso in the 1950s, so Nash would be to reggae in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

And he was just about to release the first of his two worldwide smash hits in between introducing reggae music in general and Bob Marley in particular to the world.

Once in Kingston, Sims and Nash were lent a house in the hills above Kingston by a business associate — the Jamaican record executive Ken Khouri, owner of the only recording studio on the island, Federal by name. And it was at Federal in 1965 that a singer named Hopeton Lewis recorded a song called “Take It Easy,” thus easing Jamaican music out of the fast-paced and horn-heavy ska sound and into a more bass-driven, relaxed style that came to be known as rocksteady, the immediate predecessor to reggae.

Ken’s son Paul began teaching Nash the basics of rocksteady and through their friend Neville Willoughby, a Kingston DJ and the son of Sims’s Jamaican attorney, Nash was sampling Kingston’s nightlife, and on Ethopian Christmas — Jan. 7, 1967 — Willoughby took Nash to Rastafarian musical / religious event known locally as a “grounation” hosted by an elder statesman of the faith named Mortimo Planno. (Six months earlier, on the occasion of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s state visit to Jamaica, a white-robed Planno was by his side as he descended his airplane’s gangplank.)

Planno’s home in Marley’s soon-to-be-famous Trench Town neighborhood was ground zero for disaffected ghetto youths and rebellious uptown college kids, all of them drawn to Planno’s salon-like haven full of books on African history, Rastafarianism and anti-colonial Black Power. And it was in Planno’s yard that Nash first encountered Bob Marley.

“The report that Johnny Nash gave Danny was mindblowing,” Planno would remember later. Sims remembered it the same way.

As he told Steffens: “That night, Johnny came home raving about this guy he had met named Bob Marley. He said every song he heard him sing was an absolute smash and that we should sign him immediately to our label. The next day Bob came to our house with his wife, Rita, and Bunny Livingstone and Peter Tosh, along with Planno. Bob played guitar and sang about 30 songs for me.”

And so began a five-year or so friendship / professional relationship. Years later, Sims would claim he saw in Marley the next Bob Dylan, but it seems now that he was thinking more in terms of the next Elvis. Sims was interested in Marley as a singer of sun-kissed love songs, not the religious prophet / soul rebel Marley would become. According to some accounts, Sims allowed Marley to record his rebel / Rasta songs on the side so long as he brought the love songs to him and him alone. And Sims recorded dozens upon dozens of them, but that’s another story…

Meanwhile, Nash was ready to enter the studio with his new sound, one that would bring him his biggest hit to date, but not the biggest he was destined to enjoy.

— By John Nova Lomax