When we last left the story of Johnny Nash, the singer and actor from south Houston was in Kingston, Jamaica. There he had just become transfixed with the prevalent rocksteady style of Jamaican music, a forerunner of reggae. And he had befriended future global reggae star Bob Marley and his band, the Wailers.

Nash had introduced Marley to his wheeler-dealer of a producer, Danny Sims, who quickly signed Marley and bandmates Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer to song-writing contracts with his Cayman Music publishing company. (A Sims business partner was Paul Castellano, then head of New York’s Gambino Crime Family. In part one of this series, Sims had worked with Castellano’s underboss).

Nash was ready to enter the recording studio with his new rocksteady sound. To back him, Sims and the Jamaican studio owner arranged for guitarist Lynn Taitt to lead the band. A native of Trinidad whose professional career began on the steel drums, Taitt brought a percussive sensibility to the guitar and quickly became the most in-demand rocksteady guitarist in Jamaica. That’s him on Desmond Dekker’s “007 (Shanty Town)” and the Ethiopians’ “Train to Skaville.”

And how gloriously Taitt’s intricate, popcorn-like picking melded with a tasteful smidge of strings and Nash’s glorious tenor on “Hold Me Tight,” his first global smash hit. Listen to it three times, people, and tell me if you don’t find yourself humming Nash’s scat section for days to come.

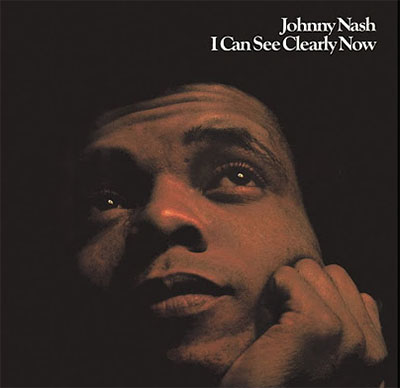

That song and Dekker’s utterly infectious “The Israelites,” which came out around the same time — not Nash’s later smash “I Can See Clearly Now” — were the songs that put reggae on the world’s radar.

And when he died in Houston in 2020, followed by his funeral at the Fountain of Praise church in the 5 Corners District, the news coverage showed that Nash had never been completely forgotten on the international stage.

And when he died in Houston in 2020, followed by his funeral at the Fountain of Praise church in the 5 Corners District, the news coverage showed that Nash had never been completely forgotten on the international stage.

“Hold Me Tight” came out in 1968 — four years of international turmoil before Paul Simon’s reggae-tinged “Mother and Child Reunion,” Nash’s blockbuster and Eric Clapton’s cover of Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff.” It frankly astonishes me today how “Hold Me Tight” has seemingly vanished into a worldwide memory hole, often mentioned only in passing or not at all in bios or Nash’s obituaries, when in fact it was the first reggae-like song to sweep the planet.

It’s not like this was some obscurity known only to cultists: Per Billboard magazine’s year-end list, “Hold Me Tight” was the 37th most successful chart single of 1968, ranking it ahead of the Rolling Stones “Jumping Jack Flash,” Marvin Gaye / Tammi Terrell’s “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing,” Sam & Dave’s “I Thank You,” Aretha Franklin’s “Think,” James Brown’s “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud” and the Beatles’ “Lady Madonna.”

It also reached the top 5 in the UK, Australia, and Canada. It’s not often included on the sort of reggae / rocksteady hits collections the way “The Israelites” is, nor is it included in soul or R&B collections memorializing that era. Maybe it just fell between the cracks.

Sims spent much of the last decades of his life marketing his voluminous trove of Marley songs, and Nash himself, a man with precious little in the way of star-in-the-making ego, didn’t push the song, either. So, like Nash’s “Let’s Move and Groove,” it’s a lost classic, albeit one that sold a ton of records.

While slightly less successful in the States, his follow-up, a rocksteady remake of Sam Cooke’s “Cupid,” reached the top 10 in England.

This was actually a re-release: it had been the B-side of “Hold Me Tight” but it still sold well to people who perhaps didn’t know they already owned it. (Doomed British chanteuse Amy Winehouse based her cover of “Cupid” not on Cooke’s original but Nash’s reimagining).

Instead of returning to America, Sims and Nash headed to London. There, and even more so in Birmingham and other British cities with high levels of Jamaican immigration, reggae was waiting to explode into the mainstream thanks to the Skinheads of yore — working-class youths of every color from slums united by a love of ska and rocksteady. (It would be many years before racism took over much of this youth movement). With Marley and Nash in tow, Sims caught a rising tsunami, with “I Can See Clearly Now” leading the way.

The song was a long time a-borning and took ages to rise to the top of the charts once released. Even today, pop historians not only can’t tell you who played on the various sessions that went into its making, and even its instrumentation remains a mystery. It was not so much recorded but constructed in studios ranging from Kingston to London to Los Angeles and Stockholm, Sweden, where Nash was working on a film shoot.

Perhaps Marley is in the mix somewhere on guitar, or Tosh, or Bunny Wailer. Rabbit Bundrick, the white Houstonian keyboard player, is in there, as are certain members of the soon-to-famous Scottish funk combo the Average White Band.

“There’s some beautifully fuzzed-out guitar,” wrote pop historian Thomas Breihan. “There’s a lithe, supple bass line. There’s a massive sunburst of horns that rolls in halfway through. I think there’s an accordion? And above it all, there’s Nash, joyous and unconcerned….And it is beautiful. Nash sells the song with an elegant simplicity. His voice hits high notes with an infectious ease. And maybe the float in Nash’s voice is where ‘I Can See Clearly Now’ draws the most from reggae. There’s a grit to the song, but it’s not the sort of grit that comes to American pop music through gospel. It’s the sort of soaring ecstasy that implies that the singer has been through some s***. It’s the darkness that the light implies.”

Perhaps with this song alone Nash was able to fuse everything he’d been working on up to that date. The song was his 100 percent his baby: he wrote all the words and those painstaking recording sessions were his idea. In it were the gospel soul vocals of his Houston childhood, the lush near-orchestral arrangement harkening to his teen years as a young Black Sinatra, and the bouncy Jamaican beat, all behind lyrics reflecting the sort of peace treaty with life one must make at key moments to keep on keepin’ on.

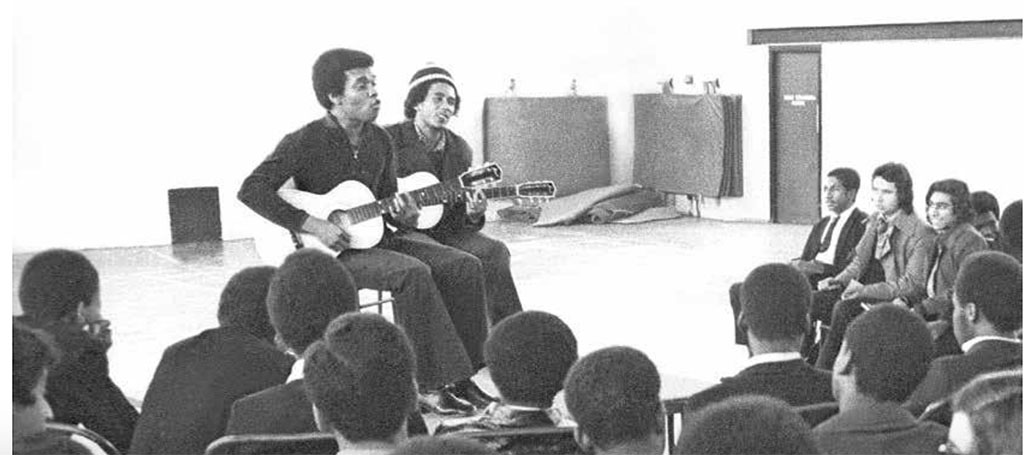

And all that took forever to record. While at these loose ends in London, Nash and Marley starred in a heartwarming little story. After a chance encounter in a London club with a school teacher, the two agreed to come in later that week and perform a secret, stripped-down acoustic show for students of London’s Peckham Manor secondary school. Some of the students there had likely heard of Nash via “Hold Me Tight” and “Cupid”, but they almost certainly had never heard the renditions of soon-to-be-immortal reggae classics like “Trenchtown Rock,” with it’s memorable lyric: “One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain.”

Nash followed that with what was one of the first live performances of “I Can See Clearly Now,” and then the two singers sat for a Q&A with the students, ages 11 to 16. The kids wanted to know what kind of car Nash drove in Texas. Always a Cadillac, he replied. Marley fielded a few questions about soccer — he was a fanatic, who kept in shape by playing the game daily whenever possible. (During a Houston visit in the mid ‘70s when he and the band were ensconced in the Plaza Hotel on Montrose Boulevard, Marley and company made their way to the practice fields at Rice University whenever they had time).

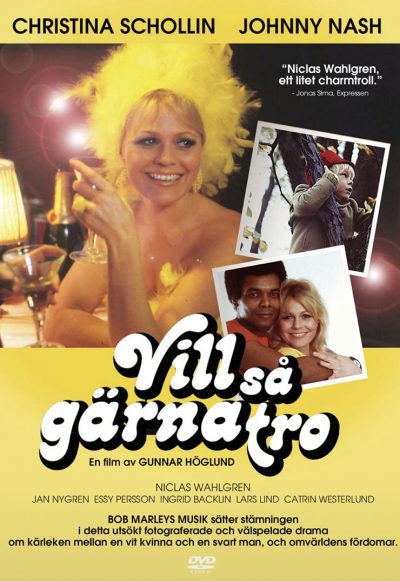

One of the reasons for Nash’s periodic absence from the hits charts was his one last stab at film acting: He played the male lead in a Swedish romance alternately called Want So Much to Believe, Love Is Not a Game and Vill så gärna tro. He wrote music for the soundtrack with Marley and Bundrick, the piano man from Houston who would be Nash’s musical sidekick for much of the early ‘70s, before he became the unofficial fifth member of the band The Who.

One of the reasons for Nash’s periodic absence from the hits charts was his one last stab at film acting: He played the male lead in a Swedish romance alternately called Want So Much to Believe, Love Is Not a Game and Vill så gärna tro. He wrote music for the soundtrack with Marley and Bundrick, the piano man from Houston who would be Nash’s musical sidekick for much of the early ‘70s, before he became the unofficial fifth member of the band The Who.

Bundrick recalls this odd sojourn on his blog: Sims, Nash, Marley, a slew of Swedish musicians, himself and a parade of Swedish groupies all under one roof, working on music for a doomed film. Marley taught Bundrick reggae while mumbling Jamaican patois imprecations about the Swedes, whom he didn’t like or respect.

“We lucked out and wrote the film theme song,” Bundrick remembered. “Sadly, nobody has ever heard it, or seen the film. We had the big premiere in Stockholm, and the next night the film closed.”

A lot of money had been riding on the film’s success, and with its utter failure, all of a sudden the money was gone. All of the money, save for what Sims could tap into on credit from the Gambinos.

Bundrick recalled that Marley had a way of appearing and disappearing as if by magic, and that was how he made his exit from the mess in Sweden.

“I really don’t know what happened to Bob,” he said. “All I do know is that his air ticket, Johnny’s guitar, and Johnny’s tape recorder all disappeared, along with Bob. Johnny never forgave him for taking his guitar. Bob disappeared as magically as he had arrived.”

But it wouldn’t take long for that scene of bankruptcy and bruised egos to resolve itself into triumph.

“I Can See Clearly Now” would hit the streets and start to climb the charts. The Los Angeles Times would call it “marvelously infectious” and “one of the year’s most inviting singles.” Robert Christgau, perhaps already claiming the title as the “Dean of American Rock Critics,” called it “a song that can get you through a traffic jam.”

Up the song climbed, surging to the very top of the charts in early November and staying there all month, until another mighty song indeed — “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” by the Temptations — was able to topple it from the throne.

All of which brings us back to the night in the Boston club in 1973, where began this saga in Part 1, when it seemed Johnny Nash was set to be one of the biggest recording stars of the 1970s and beyond.

Such was not to be. But there would be no tragedy here, no lurid and sad tale of a broke one-time star struggling with addiction or attempting ever more desperate comebacks.

What followed instead was just the story of a good man who’d had quite enough of fame and the aggravations of celebrity, happy enough to return to the south side of Houston.

To be continued.

— by John Nova Lomax