By Jayme Fraser, Houston Chronicle

New tax increment reinvestment zone could bring big changes to the area Vivian Harris bought the house with a view of Sims Bayou because her children could swim in the Olympic-size pool at a nearby park when they were not attending classes at one ofHouston’s best high schools. That was 1971.

The home is gone, and the pool was filled in. Fewer children play in Townwood Park. The once-neat lawns of her old Hiram Clarke neighbors now are trimmed with cracked sidewalks, and graying plywood covers the windows of a shopping stripHarris remembers walking to before it gained a reputation as a drug corner.

The home is gone, and the pool was filled in. Fewer children play in Townwood Park. The once-neat lawns of her old Hiram Clarke neighbors now are trimmed with cracked sidewalks, and graying plywood covers the windows of a shopping stripHarris remembers walking to before it gained a reputation as a drug corner.

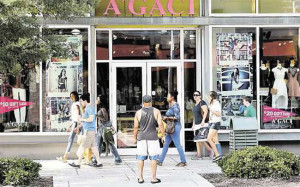

She and her husband considered moving to Katy but ended up buying a home two miles away.With all but one of the area’s grocery stores closed, she drives seven minutes to shop and dine along ShadowCreek Parkway inwest Pearland.

The town named for its pear farms has become the fastest-growing retail market in Texas. On its west end, the town has capitalized on its location at the crossroads of the Beltway andHighway 288 to become a thriving bedroom community for workers at NASA and the Texas Medical Center. Pearland Economic Development Corp. hopes to continue the growth, announcing last year more than $200 million in projects to construct or expand hospitals and medical research centers.

Tangible hope Now, after decades as a community activist, Harris finally sees tangible hope for Hiram Clarke to catchup.

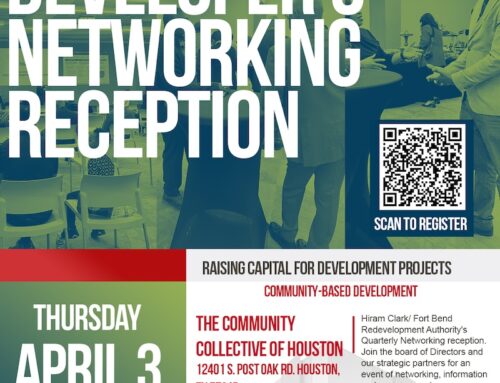

The Houston City Council and the Fort Bend County Commissioners Court approved a plan this month to boost development inHouston’s southwest corner with the creation of a tax increment reinvestment zone.

Under a tax increment reinvestment zone, property taxes generated within the zone’s boundaries are frozen at a set level.

As development occurs and property values rise, tax revenues above that level are funneled back into the zone to pay for public projects in hopes of attracting further development.

Over 30 years, the new Hiram Clarke/Fort Bend-Houston zone is expected to divert $141 million in tax revenues into such projects as road repairs, converting utility easements into park space or coordinating with developers to transform South Post Oak, Chimney Rock, Hiram Clarke and West Fuqua into commercial thoroughfares.

“See all the vacant land we have here? All of the development we could have along here?” Harris asked, pointing to an empty lot where tree branches obscure a faded real estate sign.

Harris, who sought the same types of projects in her decades as a community leader with several civic organizations, credits her new boss, District K Council Member Larry Green, with pushing for the creation of the zone.

Although Mayor Annise Parker supports the Hiram Clark zone, she said successful zones, such as Uptown or Upper Kirby, rely on commercial and residential investments, not just improved roads and drainage.

There’s nothing magical about a tax zone, Parker said.

“I’m wary of tying up a lot of the city’s tax base in the creation of (tax zones) and I’m wary of creating a (tax zone) that sets up a false expectation.” Returns of developers?

Green looks at the new zone as an assurance his district will see the same level of city investment as the 24 other areas with intact zones.

“This area has been neglected in regard to infrastructure improvements,” Green said. “We’ve gotten a lot of residential development, but our commercial is slow coming. If we incentivize it, they would come.”

“This area has been neglected in regard to infrastructure improvements,” Green said. “We’ve gotten a lot of residential development, but our commercial is slow coming. If we incentivize it, they would come.”

Joshua Sanders, executive director of Houstonians for Responsible Growth, a nonprofit that represents developers, said the reinvestment zone, coupled with changes to the city’s development rules and a new state-created management district, could bring developers back within city boundaries by proving Houston is as committed to maintaining the area as the neighboring suburban governments.

“Many businesses are choosing to go across the highway to Pearland,” Sanders said. “Once you push that far out… all these suburbs have invested more recently in infrastructure than the City of Houston has.”

As the city doubled its land area with a series of massive annexations in the 1950s and ’60s, workers at the booming Medical Center escaped city hubbub down highways 90 and 288 to new ranch homes in Hiram Clarke. City planning and development dollars, however, remained focused on the downtown core and western sprawl in the decades that followed.

In Brazoria County, Pearland persisted as a primarily agricultural community until the 1980s and 1990s, when growth at NASA and the completion of the south Beltway drove development. Pearland’s population tripled between 2000 and 2010 as local officials and a new economic development corporation focused on investments that outpaced the City of Houston’s spending nearby.

Matt Buchanan, president of the Pearland Economic Development Corporation, welcomed the Hiram Clarke reinvestment zone as an opportunity to help the entire metro south side. “Hopefully, Pearland can be an anchor here,” he said. Harris hopes the revival of her community could shift the balance. “I feel hope. For the first time in a long time.”