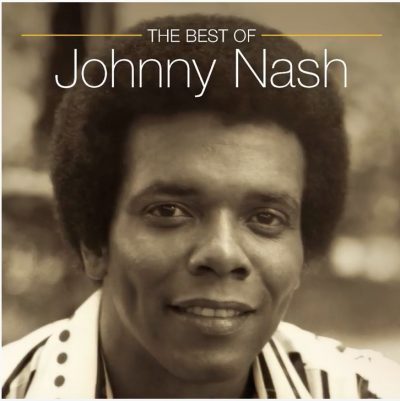

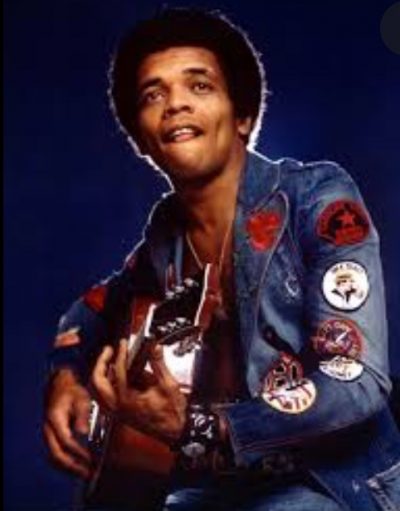

On a fall night in Boston in 1973, singer Johnny Nash from Houston had the world in his hands. Though only 30 years old, he had a string of hits dating back to the ‘50s already behind him, though none as big as his transcendent “I Can See Clearly Now.”

Now, that one had been a monster — topping the charts in America, mercifully surging past Chuck Berry’s cringeworthy “My Ding-a-Ling” and “Ben,” Michael Jackson’s ode upon a sewer rat. With a month atop the charts, “I Can See Clearly Now” enjoyed pole position for as many consecutive weeks as any single released that year except Roberta Flack’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” tying for second with, among others, “American Pie” by Don McLean and beating out “Horse With No Name” by America and “Lean on Me” by Bill Withers. It took the Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” to topple the Nash classic.

Now, that one had been a monster — topping the charts in America, mercifully surging past Chuck Berry’s cringeworthy “My Ding-a-Ling” and “Ben,” Michael Jackson’s ode upon a sewer rat. With a month atop the charts, “I Can See Clearly Now” enjoyed pole position for as many consecutive weeks as any single released that year except Roberta Flack’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” tying for second with, among others, “American Pie” by Don McLean and beating out “Horse With No Name” by America and “Lean on Me” by Bill Withers. It took the Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” to topple the Nash classic.

(If you are getting the notion that 1972 was a killer year for pop music, we’re only halfway through: It also saw the releases of “Me and Mrs. Jones,” “Oh Girl,” “I’ll Take You There,” and “Let’s Stay Together,” and that’s just to mention the R&B crossover smashes).

Nash had just hosted the late-night TV rock concert program Midnight Special, where he joked that he hoped the audience had not been expecting Johnny Cash. He had assembled a crack road band — four young white boys from Houston who called themselves the Sons of the Jungle, most of whom would go on to long and distinguished careers for some of the biggest names in popular music.

Backstage at Paul’s Mall club in Boston, Nash told an interviewer from the esteemed African-American weekly the New Pittsburgh Courier that future shows would see the Sons of the Jungle augmented with a horn section of “four Ghanaian brothers who can really cook.” As for his abortive tour with Sly and the Family Stone that had just foundered — they were supposed to have done 14 shows and only completed two — the fiasco was on Sly’s band, not Sly himself — and certainly not Nash.

After questions about his marital status (single), his favorite female artist (Aretha Franklin) and his astrological star sign (Leo), talk turned to the reggae tinges in Nash’s sound. The genre was so little known or understood in America at that time that the paper misspelled Bob Marley’s name (Marly). Since the late ‘60s, all of Nash’s singles had been spiced, Caribbean jerk-style ,with the sounds of Kingston, Nash’s home-away-from home for several years. How did you get into the reggae sound so heavily, the interviewer asked.

“I don’t prefer to be categorized as a reggae artist, but to listen to my sound one can readily hear the influence of reggae,” Nash said. “During my earlier career years I traveled to Jamaica and picked up the reggae sound fast and earnestly. I did not catch on here in the States as a reggae artist, but as a singer because what I do is a blend of reggae, soul and jazz-rock. I have tried to maintain an international flavor in my music because touring the States, the Caribbean, Europe and Japan, I have found that all people love music and music means everything in my life.”

The interview closed with Nash’s hopes for the future. Since 1960, Nash had moonlighted as an actor, and he was hoping for a stateside release of a film he’d just completed in Sweden.

The interview closed with Nash’s hopes for the future. Since 1960, Nash had moonlighted as an actor, and he was hoping for a stateside release of a film he’d just completed in Sweden.

That never came to pass, nor did the Ghanaians ever join the Sons of the Jungle. Nobody would have guessed it at the time, but that night in Paul’s Mall was at or very near the apex of one of the most intriguing, maddening, and picaresque careers in American pop music. Though his talents never diminished, the chart hits would dry up, and by the end of the 1970s, which had started with such promise, his career — on the road, in the studio, and on the silver screens alike — would effectively be over, and by choice, rather than because of the usual pitfalls of the touring musician.

“I Can See Clearly Now” would come to dominate his legacy to the point where even music fans and historians you would think would know better came to file him in the one-hit wonder bin. As we shall see, that is both a shame and a sin, and just plain wrong to boot.

* * *

Johnny Nash’s life began and ended in a 10-mile radius on Houston’s south side. John Lester Nash was born on Aug. 19, 1940, in Third Ward and funeralized at Fountain of Praise church in the Five Corners District on Oct. 15, 2020.

Nash now sleeps eternally just a little to the south, in Pearland’s Houston Memorial Gardens, not far from the final resting places of James Brown sideman/solo artist/funk architect Bobby Byrd, fabled Yates Lions running back Johnny Bailey, Houston Cougar backcourt scoring machine Rob Williams, Astros legend (and former 5 Corners resident) Jimmy “the Toy Cannon” Wynn — and George Floyd, whose 2020 funeral also took place at the Fountain of Praise.

Per legend, toddler Johnny Nash used to cry songs from his cradle. Per fact, he made his public debut at age 4, singing “Away in a Manger” in a Christmas pageant. He rapidly became a star of the choir at Houston’s Progressive New Hope Baptist Church at the corner of Elgin and Delano, but according to his family, he was discovered on the links at Hermann Park, where, as a 14-year-old singing caddy, he warbled his way onto Matinee, a local variety show airing on KPRC-TV.

Houston stages — as one newspaper put it, these ran the gamut from “clubs, churches and teas” — couldn’t hold him for long; by 16 he’d been discovered on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts, an Atomic Age precursor to American Idol that also helped launch the careers of Leslie Uggams, Tony Bennett, Patsy Cline, Pat Boone and Hee Haw’s Roy Clark, among many others.

The Godfrey show led him to a deal with the ABC-Paramount record label, and Nash’s major-label debut, a 1956 78-rpm single called “A Teenager Sings the Blues,” found him in a plinking piano-and-boozy-muted-trumpet setting, drowning his sorrows in sarsaparilla and singing lines like, “No don’t play the jukebox / please don’t speak her name / I guess I’ll have a soda, then one more of the same / oh, I’ve got a heartache, right down to my shoes / and a teenager sings…the blues.”

Oddly, Nash’s voice is about two octaves deeper than the swooping tenor will all remember him for now; when scribes of the time described him as a baritone, it was not a result of deafness or musical ignorance. His first chart hit — Doris Day’s “A Very Special Girl” — found him crooning the sort of lush, smooth pop of the late 1950s that whisks you away to a leafy suburb in autumn, one you are driving through in tranquil bliss behind the wheel of a gleaming new Cadillac, resolutely tuning out Cold War paranoia. Such music is so of its time and only of its time, it’s the one genre every thrift store in America always has in abundance. There has been no renaissance for the music of Lawrence Welk, Anita Bryant, Ferrante & Teicher or Johnny Mathis, an artist whom ABC thought Nash could compete with well.

Oddly, Nash’s voice is about two octaves deeper than the swooping tenor will all remember him for now; when scribes of the time described him as a baritone, it was not a result of deafness or musical ignorance. His first chart hit — Doris Day’s “A Very Special Girl” — found him crooning the sort of lush, smooth pop of the late 1950s that whisks you away to a leafy suburb in autumn, one you are driving through in tranquil bliss behind the wheel of a gleaming new Cadillac, resolutely tuning out Cold War paranoia. Such music is so of its time and only of its time, it’s the one genre every thrift store in America always has in abundance. There has been no renaissance for the music of Lawrence Welk, Anita Bryant, Ferrante & Teicher or Johnny Mathis, an artist whom ABC thought Nash could compete with well.

After the singing cowboys of the previous generation, the teen idols of the ‘50s were among the first multimedia superstars. There was Elvis, of course, but he had competition from Frankie Avalon, Paul Anka, and the tragic Frankie Lymon of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” fame, Nash’s only competition as America’s first Black teen idol.

Lymon would die of a heroin overdose at 25 in 1968, just as Nash’s career was launching into its second act, but for the moment, Lymon’s much more au courant doo-wop sound made the schmaltzy arrangements Nash’s ABC-Paramount producers saddled him with sound utterly square.

In 1959, however, Nash branched out into film, starring in Take a Giant Step, an adaptation of a stage play by Louis S. Peterson, the first Black playwright to land his work on Broadway. Per a Hollywood legend that Nash himself never verified, one of his televised performances persuaded executive producer Burt Lancaster to give him the starring role of Spencer Scott over the young man who played him onstage — 17-year-old Louis Gossett Jr.

Co-starring Ruby Dee, this coming-of-age drama about the struggles of a Black teen to cope with growing up in a white milieu, the film –- censored and edited by the time of its release — was panned by the New York Times, though Nash’s performance was generally well-received, garnering him a Silver Sail Award from the esteemed Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland.

Meanwhile, he was continuing to record on an ad hoc basis, releasing singles for Warner Brothers, and Argo, the soul/ jazz / pop division of the legendary Chicago-based Chess label, home of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Etta James and the Dells.

By then, he was extricating himself from the syrupy strings in favor of a lean and efficient and far more organically bluesy sound. On these singles, he was backed by the Chess / Argo house band, whose members included (among other young session players whose eventual credits are too numerous to mention) the rhythm section of drummer Maurice White and bassist Louis Satterfield, who would go on to form the cornerstone of Earth, Wind and Fire.

He was also working with Johnny Pate. As Joe Scott was to Don Robey’s Duke-Peacock Records here in Houston, so the Army Band-trained Pate was to Chi-town. Simply put, Scott and Pate were among the top producers and arrangers on the planet. Pate would go on to help craft the mature Curtis Mayfield sound and also worked with Bobby Bland after Scott and Bland parted ways. And oh yeah, Pate also produced and arranged BB King’s Live at the Regal, arguably the greatest live blues record of all time.

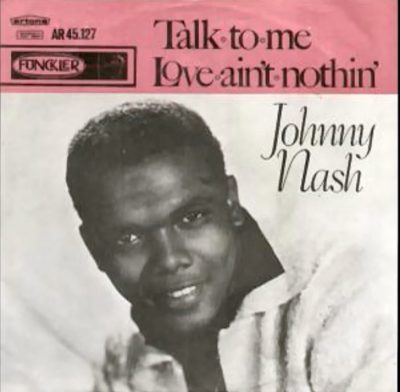

Though Nash was still sticking close to the low end of his amazing register, his long and abiding love for Sam Cooke was just beginning to come to the fore, as heard here on “Love Ain’t Nothing (But A Monkey on Your Back).”

By the early-to-mid 60s, Nash was spending more time in New York, which is where he landed the lead vocal for the theme of animated show “The Mighty Hercules,” produced by Trans-Lux (of Felix the Cat and Speed Racer fame).

And it was in New York where life would start coming at him fast. It was there he met producer/svengali Danny Sims, and within a year or so there would be more hit records and an exile-turned-sojourn in Jamaica, where Nash and Sims would lay the groundwork for Bob Marley and, by extension, reggae music to leap out of Kingston and envelop the world. Along the way, Nash would etch his name in the American songbook, and then, well, he would just ease off into the embrace of home and hearth and friends and family in Houston.

— by John Nova Lomax